Assessing What Matters Most to Children: Parenting

Momentum has gathered over the last decade toward collecting evidence to prove outcomes in the early childhood field. Funders and taxpayers want proof that the services they pay for have the intended outcome. The fairest way to evaluate a program is to see if it has met its intended goals. Most programs with the goal of healthy child development and well-being, school readiness or preventing child abuse and neglect include promoting nurturing parenting among their goals, because “Young children experience their world as an environment of relationships, and these relationships affect virtually all aspects of their development – intellectual, social, emotional, physical, behavioral, and moral” (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004).

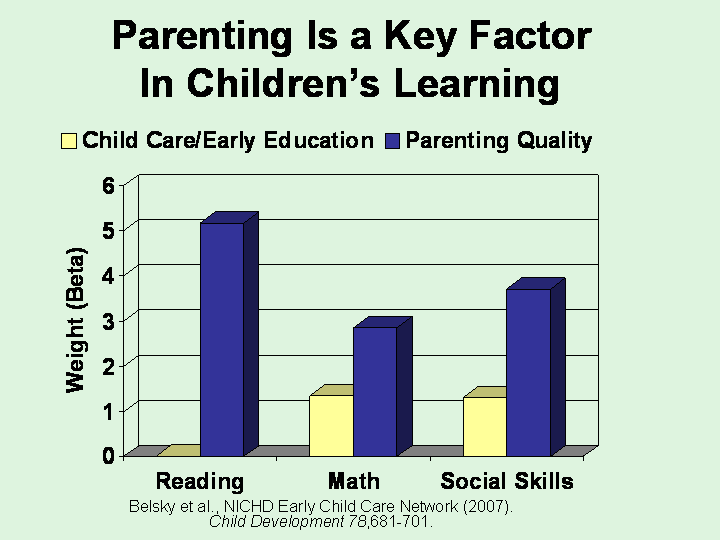

Parenting Quality is Key Factor in Children’s Learning

Research is clear that parenting quality is a key factor in attaining these goals. For example, a longitudinal study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Early Child Care Research Network, designed to investigate the impact of different types of early childcare on children’s learning over time, found that parenting was the predominant factor in children’s 5th and 6th grade school achievement. This long-term study of over 1000 children included a range of childcare, including center-based settings like Head Start. Maternal behavior was assessed as a statistical control variable; however, the study concluded that “Parenting was a stronger and more consistent predictor of children’s development than early child care experience.” As shown in the figure, parenting quality had a much stronger impact on children’s achievement across several domains [Belsky, et. al., (2007) Are There Long Term Effects from Early Child Care? Child Development 78:681-701].

The overwhelming results proving the importance of parenting quality led James Heckman, Nobel Laureate in Economics, to conclude, “The proper measure of child adversity is the quality of parenting — not the traditional measures of family income or parental education … The scarce resource is love and parenting—not money” (Promoting Social Mobility, Boston Review). For more on James Heckman’s extensive work see the Heckman Equation website.

The evidence that parenting is a predominant factor in children’s healthy development has been used by political interests to attack preschool programs (a recent example). Rather than attacking the early childhood classroom, we view it as a missed opportunity to do more for children, particularly with those from families with low incomes and high risk circumstances. By adding goals of enhancing parenting practices to be more nurturing, early care and education programs can better serve children. The goal of enhancing nurturing parenting is far more challenging than the goal of parent engagement that center-based programs now strive to meet. Admittedly, addressing parental behavior is very challenging, but a variety of interventions have shown that, with support, parents can improve their behavior to benefit their children (for a review follow this link).

Early childhood programs should set goals reflecting the best evidence of what matters to children. Based on the overwhelming evidence, programs should include promoting parenting quality among their goals. In school it is well known that what gets tested gets taught. Similarly outside of the classroom, what gets assessed gets focus. If parenting goals are so important, shouldn’t they be assessed? If parenting is so important, why don’t more early childhood programs measure parenting, when practical validated parenting assessment tools are available?